Snake bites and envenomations - What advice tourists must know when they travel to Australia?

There are many snakes in wild regions of the planet. In particular, when we look at Australia, snake bites are a common issue rural paramedics and hospitals face. It is very useful to be well aware of what to do in case of snake bites.

The main problem is always if the biting snake released a deadly venom or not. The article that follows is written by Tim Leeuwemburg, a Rural Doctor on Kangaroo Island, South Australia on Kangaroo Island. The situation is usually like as follows: “Yes, there was a snake. Yes, there is a bite mark. But is there envenomation? Who knows….”

Snake bites: who gets bitten?

Snakes may come close to humans to hunt mice, steal eggs or be close to water. Warm weather increased tourists on the Island..plus of course alcohol, late nights, farm activity etc mean that there is more chance for humans and snakes to coincide.

But despite their reputation, snakes are generally shy creatures and would prefer to evade humans than interact with them. To be frank, humans are not primary prey for snakes! They’d rather conserve their venom for something they can eat…like a mouse, small lizard or similar.

A snake’s first defence will be to move AWAY from a human if possible. If threatened, they may rear and hood, to make themselves look large and threatening.

Not surprisingly most snake bites happen when people either surprise a snake (tread on it!) or provoke it (try to kill it, relocate it or generally muck with it).

Snake bites: what should I do if I get bitten?

The first thing to do in a suspected snake bite is to apply a pressure immobilisation bandage.

Every home, car or workplace should have access to a pressure immobilisation bandage. A simple crepe bandage or two would work fine. Apply firmly over the bite site, then wrap the limb from distal (fingers or toes) to proximal (up the limb as far as can go).

The bandage should be applied firmly – as if for a sprained ankle – not so tight as to stop blood flow to the peripheries! Unlike bandaging or splinting traumatic wounds (where we ‘splint-to-skin’), it’s probably best to leave clothes on and apply the bandage over the clothing.

Some neat dedicated snake bite bandages have visual markers to help guide how firmly to apply the bandage. For my money, a simple OLAES Modular Bandage or Israeli/Emergency Bandage would suffice for rural community members and also doubles as an excellent device for other uses.

Splint the limb if possible to reduce movement – the venom typically spreads through the lymph initially.

Do NOT apply a tourniquet.

Do NOT try to cut out or suck out the venom.

If in doubt, ring 000 and take the call handlers advice.

Once PIB is on and splints applied, the next priority is to transport the casualty to Hospital.

The first point of call should be SA Ambulance – they may send a local crew or, if remote, organise a primary retrieval from the scene.

Should I capture or kill the snake? For identification purposes?

No. People often think that it is necessary to bring snakes into the Hospital for identification purposes and to help guide the choice of antivenin. It’s true that herpetologists might want to count anal scales to identify the snake. But not most doctors.

Of course, we’ve got it relatively easy on Kangaroo Island – we only have two types of the snake (the tiger snake and the pygmy copperhead)….and the antivenin we use is the same for both! Of the two, the tiger snake is reportedly more likely to bite.

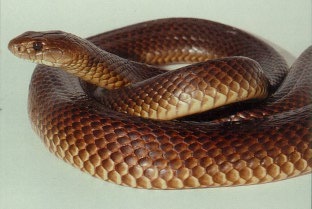

In other locations in Australia, there are far more options for envenomation – the brown snake is responsible for most snakebite deaths Australia….and of course, we have more deadly snakes here than in the rest of the world!

But we don’t need to see the snake.

All hospitals have access to a venom detection kit – this doesn’t actually tell us if the victim is envenomated or not…rather it helps us to identify WHICH antivenin to use.

Many hospitals have polyvalent antivenin which will cover major local snake species.

So – how do I know if I’ve been bitten?

Short answer? You don’t. It can be really tricky. Presentations may vary from the so-called “dry bite” (snake+fang marks but no venom injected) through to sudden collapse with no warning (unwitnessed bite or unreliable historian, with severe envenomation and death).

Hopefully, most snakebite presentations will be somewhere in the middle “There was a snake – it struck me – there’s a bite mark – I feel unwell”. But long and short, if you THINK you’ve been bitten by a snake, we will believe you!

Snake bites: what happens at the hospital?

As mentioned above, the Venom Detection Kits aren’t used to determine if envenomated or not – they are used to guide the choice of antivenin.

If someone arrives in the Rural Hospital with a PIB in place, we are unlikely to remove it – there have been reports of sudden collapse as the previously contained venom is now disseminated.

Instead, the patient is transported to a place that can monitor the patient. This means regular blood tests for coagulopathy and requires a 24/7 lab. This is why pretty much all suspected snake bites in rural South Australia will be transported to a tertiary centre (sites with on-site antivenin AND 24/7 lab facilities may elect to monitor stable patients).

Of course, there ARE ways to check for envenomation – most snakes will give rise to either neurotoxicity or coagulopathy. Nerve or blood problems.

A patient with slurred speech, blurred vision or obvious neurological symptoms and signs on a background of suspected snake bite can be assumed to be envenomated and antivenin may need to be given – usually in conjunction with the State-based Toxicology experts (Julian White & Scott Weinstein) based at the Women’s & Children’s Hospital in Adelaide. these guys offer a 24/7 service and are always super helpful and friendly when discussing possible snake bite and management.

Ditto someone who has evidence of bleeding disorder e.g.: bleeding from gums, blood in urine etc. This may indicate coagulopathy and antivenin may be required. NB Rural doctors should be aware that point-of-care INR testing is NOT reliable for demonstrating clotting disorders due to envenomation.

If there are clear signs of envenomation, don’t panic – the Hospital has antivenin. So we can treat you. But antivenin is not something we’d give ‘in case’. Rather we reserve to use for those who have signs of envenomation.

What’s with the glass test tubes?

An old rural doc trick is to use ‘whole blood clotting time’ – take a 10ml sample of the patients’ blood and at the same time, take a 10ml sample of a colleagues blood and place each in a glass test tube (with no additive/preservative). Gently agitate over twenty minutes, then invert. A marked disparity between clot formation may indicate a consumptive coagulopathy in the patient blood.

Of course, this takes 20 mins or so to do and should NOT delay resuscitation and transfer. It certainly can’t be used to ‘rule out’ envenomation…rather to perhaps fill in the time whilst waiting for the transport platform to arrive and perhaps allow early consideration of antivenin administration before things turn ugly…

I don’t think that performing this test is something that should delay the transfer.

Snake bites: briefly, what should I do?

- stay still and call 000

- apply a Pressure Immobilisation Bandage

- splint the affected body part

- don’t attempt to kill or capture the snake

- expect to be transported to a tertiary hospital ASAP; this may be via local rural hospital

- don’t let anyone faff around with fancy blood tests or ‘whole blood clotting’ as a prelude to transport – if thinking ‘snakebite’ we need to move you

If you have evidence of envenomation, the local Hospital has antivenin for local snakes. We will only give this if there is clear evidence of envenomation and in conjunction with the Toxinology experts at WCH. Don’t let anyone take the bandage off until you’re in a tertiary hospital. Even once the badge is off, walk around a bit to make sure previously contained venom isn’t now free to circulate!

On the author: Tim Leeuwenburg

READ ALSO

What to do in case of snakebite? Tips for prevention and treatment

A new species of brown recluse spider discovered in Mexico: what to know about his venomous bite?

REFERENCES