Fractures of the growth plate or epiphyseal detachments: what they are and how to treat them

Fractures of the growth plate or epiphyseal detachments: the growth plate cartilage allows the bones to grow longer but is a particularly fragile area of the bone. It is a frequent site of fractures in children

CHILD HEALTH: LEARN MORE ABOUT MEDICHILD BY VISITING THE BOOTH AT EMERGENCY EXPO

The growth plate: what is it?

Children’s bones differ from those of adults in several ways, but mainly because they have the opportunity to grow.

The growth of the long bones (such as the femur, tibia, fibula, humerus, radius, ulna and also the small bones of the hand and foot), is done by means of the growth cartilage, a structure present in a very specific region, located between the metaphysis and the epiphysis, i.e. near the ends of the bone.

The growth cartilage allows the bones to lengthen until the child reaches its final height.

The growth cartilage or physis or growth plate is the last part of a child’s bones to ossify when they reach the end of their growth and is until then a more fragile area of the bone, which is therefore more vulnerable to fractures.

A fracture of the growth plate, also known as epiphyseal detachment, can occur as a result of direct or indirect trauma.

If the bone fractures at the growth plate, the epiphysis will inevitably detach from the metaphysis of the bone.

EPIPHYSEAL DETACHMENTS

Epiphyseal detachments account for between 15% and 30% of all childhood fractures and are also among the most worrying, as the length and shape of the mature bone depends on the correct functioning of the growth plate.

Correct and timely treatment is therefore essential in order to reduce the risk of future deformities related to the axis and length of the limbs involved.

If well treated, complete healing is possible in the majority of cases, but there remains a hypothetical long-term risk, linked to the fact that epiphyseal detachment still produces damage to the growth cartilage that can alter limb growth in an unpredictable way.

Statistically, epiphyseal detachments occur more often in males, usually as a result of direct trauma during sporting activities, with a peak around second childhood.

The sites most frequently involved in growth plate injuries are the long bones of the fingers, the wrist (radius and ulna ends facing the hand) and the leg bones (tibia and fibula).

How do fractures of the growth plate manifest themselves?

Severe and persistent pain, accompanied by restriction of movement and the appearance of swelling characterise these injuries.

Forms with a higher degree of decomposition also show a deviation from the normal anatomical profile of the affected limb and an obvious swelling and are therefore easier to suspect than the less severe forms, which in some cases can go unrecognised as they only cause a less pronounced pain and a slight limitation of movement.

For this reason, it is important not to underestimate the situation if there is persistent pain following a major trauma and to consult a specialist, who will assess whether an X-ray examination is necessary.

Fractures of the growth plate – how is it diagnosed?

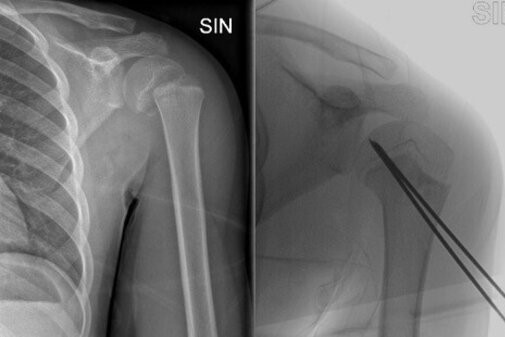

The standard X-ray in two projections (commonly called “x-ray”) is almost always sufficient to identify the type of lesion.

The earlier the diagnosis is made, the better the chances of applying the correct treatment in time, thus improving the prognosis.

If more detail is needed, the doctor may order other imaging tests such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT), which can better show the soft tissue or give a three-dimensional view of the fragments.

The type of epiphyseal detachment, its degree of decomposition and location, as well as the age of the child, have a fundamental influence on the prognosis and treatment of these lesions.

In fact, the fracture can pass all the way through the growth plate, or it can cross it and involve the downstream region (epiphysis) or upstream region (metaphysis), configuring what are called mixed epiphyseal detachments.

The growth plate can also suffer more or less symmetrical compression damage.

All these different options with their subgroups have been accurately described in the Salter-Harris classification and are universally known.

How growth plate injuries are treated:

Lesions that remain perfectly composite are classically treated by immobilisation with plaster casts.

In decomposed epiphyseal detachments, the fracture stumps must first be realigned, usually by means of a reduction manoeuvre.

The reduction of epiphyseal detachments should ensure that the epiphysis, growth plate and metaphysis return to their normal position and relationship with each other.

Being a painful manoeuvre for the small patient, it is preferably performed under sedation.

More severe and potentially less stable epiphyseal detachments, on the other hand, must be managed in the operating theatre promptly.

In these cases it is possible to carry out all the manoeuvres necessary to realign the epiphyseal detachment, taking advantage of the patient’s muscular relaxation under anaesthesia, in total absence of pain and with the aid of continuous radiographic control.

The most complex fractures may not realign even in these favourable situations and then it is necessary to proceed with surgical incisions that allow the bone to be reached by removing the obstacles that prevent reduction. This is known as ‘cruel reduction’.

Once perfect realignment has been achieved, it is important to stabilise the epiphyseal detachment as stably as possible in order to encourage consolidation and the resumption of normal growth cartilage function.

Lesions that are considered to be more stable may require a plaster cast for 3 to 6 weeks, while unstable and complex lesions require surgical blocking of the fragments, which is generally done by inserting metal wires that are then combined with plaster casts to limit movement.

The wires are then removed, usually after 4 weeks, after periodic clinical and radiographic checks to confirm healing. Depending on the location and severity of the injury, a gradual return to normal activities will be planned.

Stiffness and initial limitation of movement can be expected in the early stages of recovery and in some cases may benefit from physiotherapy or the use of specific braces.

Periodic checks should continue for a few years after healing in order to verify the normal recovery of the function of the growing cartilage.

It is possible for bone bridges to form that arrest growth or cause a deviation of the bone concerned or, on the other hand, it is possible for the fractured limb to be overstimulated, and over the years it will tend to grow more than the limb on the opposite side, resulting in dysmetria.

In such cases, the orthopaedist will be able to re-intervene to avoid more serious deformities.

Read Also:

Emergency Live Even More…Live: Download The New Free App Of Your Newspaper For IOS And Android

Bone Cysts In Children, The First Sign May Be A ‘Pathological’ Fracture

Fracture Of The Wrist: How To Recognise And Treat It