Acute abdomen: meaning, history, diagnosis and treatment

The medical term ‘acute abdomen’ refers to a clinical picture of very intense and sudden pain in the abdomen

In the medical field, some dispute the term acute abdomen, preferring the term ‘abdominal acute pain’ to emphasise the role of the main symptom, pain.

The acute abdomen is an alarm bell that should not be underestimated, as it often appears in the case of serious complications in the course of certain diseases, not exclusively abdominal, such as intestinal perforations, endo-cavitary haemorrhages and acute necrotic pancreatitis.

At other times, the acute abdomen may instead constitute one of the moments in the course of a pathological event, presenting itself in the case of acute cholecystitis, renal colic and acute appendicitis.

Classification of causes of acute abdomen

Although it occurs in the abdomen, acute abdomen is not necessarily linked to diseases of the organs contained in this cavity and thus it is possible to distinguish causes

- endo-abdominal: when the organs located there are involved: intestine, liver, pancreas;

- extra-abdominal: from distant organs: kidney, thoracic aorta, heart, lung;

- systemic or general: in the case of pathologies not specifically linked to one organ but involving the organism as a whole.

Such a varied aetiology explains the frequency, calculated at more than 10%, with which it is observed in emergency room services.

It may resolve spontaneously or, in cases of internist relevance, after pharmacological therapy, but most often requires prompt surgical treatment and therefore constitutes one of the most frequent causes of admission to emergency surgery departments.

Symptoms related to acute abdomen

The acute abdomen manifests itself with symptoms in which pain is predominant.

Other signs are variously associated with it, such as vomiting, disturbance of bowel function, motor restlessness, fever, tachycardia, hypotension and even shock.

Pain

It is the most important symptom and represents the response to stimuli of a

- chemical: substances released during inflammatory or necrotic processes or coming into contact with the peritoneum following perforations or haemorrhages (hydrochloric acid, blood, bile, pancreatic juice)

- mechanical: due to distension of the capsule of parenchymatous organs, acute dilatation of hollow organs or spasm of their smooth muscles, compression and infiltration of sensory nerve endings.

Pain is an important symptom but the complexity of its genesis and the variety of its manifestations make it unreliable for the purposes of a diagnosis of certainty.

It must however always be carefully investigated from an anamnestic and clinical point of view because for some diseases its characteristics may be pathognomonic:

A) time and mode of onset: the pain may appear suddenly, with a brutal character, rapidly reaching its acme, as in the case of an intestinal perforation (the patient often refers to it as a ‘dagger blow’) or an intestinal infarction, at other times it may have a less intense character and a more gradual evolution as in the case of an appendicular inflammation.

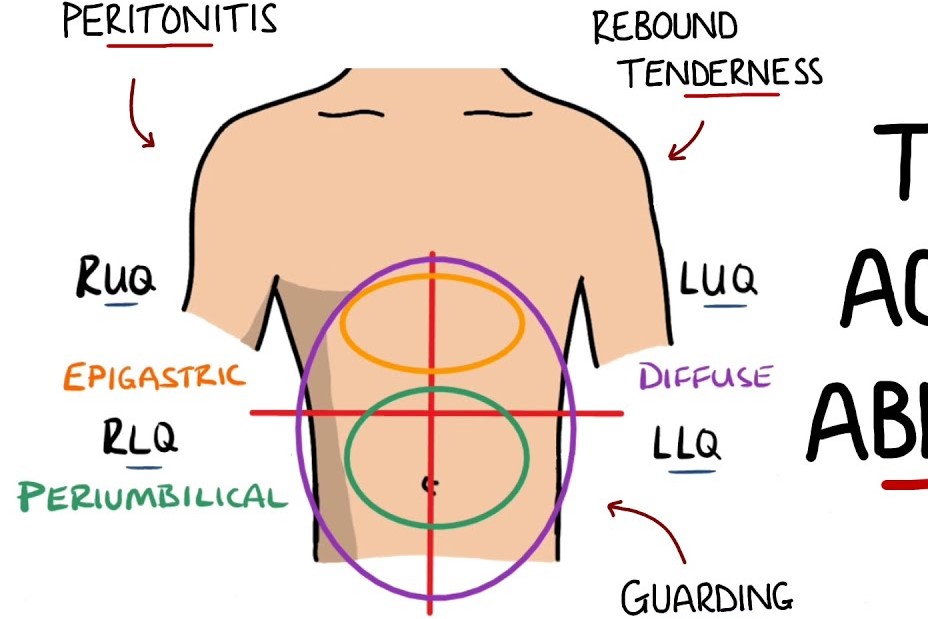

B) location:

- The pain, in the initial stages, may be localised in the quadrant representing the skin projection of the organ involved. An acute cholecystitis may begin with pain confined to the right hypochondrium; the perforation of a duodenal ulcer with pain in the right hypochondrium or epigastrium. In ovarian pathology the pain will be localised to the corresponding iliac fossa; to the right iliac fossa, or ileo-cecal fossa, the painful symptomatology of an appendicitis or of a right ureteral calculus will also be referred.

- In other cases the pain, initially vague, deep and referred to the midline, will later localise to a specific area. An example of this is acute appendicitis, which may present with a diffuse, ill-defined, periumbilical pain (protopathic visceral pain) and later circumscribe to the right iliac fossa, its anatomical site (epicritic parietal somatic pain secondary to parietal peritoneal involvement).

- Other times the spatial reference of the pain may be misleading, leading to even serious diagnostic errors. A perforation of the stomach usually begins with a violent ‘dagger-like’ pain in the epigastric region which, as time passes, may be localised to the ileo-cecal fossa (where the peritoneum is stimulated by the gastric juice that has collected there due to gravity after escaping from the perforation), simulating pathologies more referable to that area such as appendicular or ovarian. In the course of pancreatitis or cholecystitis the pain may be referred to the spinal or right subscapular region respectively. Frequent abnormalities of position and morphology of the vermiform appendix are responsible for atypical appendicular pictures with pain in the right hypochondrium simulating a biliary colic, or pain localised in the retro- or suprapubic region suggesting a bladder or gynaecological pathology, linked to the excessive length of the organ that projects its tip into the subhepatic or pelvic regions respectively.

C) nature and type: the pain may be continuous, typical of inflammatory pathologies or intermittent with the characteristics of colic, if linked to diseases of the hollow viscera such as the intestine, ureter, biliary tract. It presents as cramp-like in the initial forms of intestinal obstruction, belt-like or rod-like in pancreatitis or piercing ‘dagger-like’ in perforative pathologies.

D) intensity and evolution: pain, being a subjective symptom, is experienced differently by patients in relation to their tolerance capacity or perceptual threshold. However, for some pathologies, a necrotic pancreatitis, the dissection of an aortic aneurysm, an intestinal infarction, the pain picture is dramatic.

E) Evocability. Pain as a symptom is subjective but can also be assessed as an objective sign by evoking it with particular manoeuvres or by exerting pressure in specific areas:

- Murphy’s manoeuvre. It consists of deep palpation of the right hypochondrium by bending the fingertips of the fingers so as to hook the costal arch. The deep inhalation to which the patient is invited by lowering the diaphragm allows contact of the fingers with the hepatic rim and the gallbladder. In the presence of gallbladder and biliary tract pathology, the manoeuvre causes pain and forces the patient to stop inhaling. The manoeuvre is called positive in this case.

- Giordano manoeuvre. The examiner strikes with the ulnar edge of the hand the renal loggia of the patient while seated and with the trunk flexed. It is positive when the blow causes violent pain and this occurs in the presence of renal or ureter pathologies.

- Blumberg manoeuvre. This manoeuvre consists of gently resting the fingers of the hand on the patient’s abdominal wall, sinking it gradually (first phase) and then lifting it suddenly (second phase). It is said to be positive if the pain the patient feels during the first phase of the manoeuvre and which is modest, in the second phase increases in intensity becoming violent. It is a direct sign of peritonitis.

- Rovsing manoeuvre. Pressure is applied with the fingers and palm of the hand at the level of the left iliac fossa. Then the hand is moved progressively upwards to compress the descending colon. If the manoeuvre evokes pain in the right iliac fossa, it is said to be positive and is an inconstant sign of acute appendicitis.

- psoas manoeuvre. In cases where the patient holds the thigh flexed over the pelvis in an antalgic position, forced extension of the limb evokes pain in the iliac fossa on the same side. Another manoeuvre, which is positive in appendicitis, consists of compressing the right iliac fossa while simultaneously raising the patient’s limb with a rigid knee. The resulting contraction of the psoas muscle exerts pressure on the cecum and the inflamed appendix, causing pain.

- pressure on specific points: on McBurney’s point in case of acute appendicitis, in the Douglas excavation that can be reached in the female with a vaginal exploration and in the male with a rectal exploration, in case of peritonitis.

Other symptoms of acute abdomen

A) Vomiting.

- May present as a neurovegetative phenomenon associated with nausea and sweating.

It is often accompanied by pain that subsides after the vomiting episode. It is a typical phenomenon of biliary colic.

In some cases it marks the symptomatic onset of the disease. Nausea and vomiting are often the first and only symptoms of early-stage appendicitis. This can lead to a hasty diagnosis of ‘indigestion’. Also contributing to this error, which can have serious consequences, is the appearance at a later date of a pain of the type that we have called visceral protopathic and which is therefore reported as being deep and localised in the peri-umbilical area and not in the right iliac fossa, the anatomical site of the appendix!

- It may be obstructive in nature. In these cases, the type, quantity and quality of vomiting will serve to identify the level of the occlusion.

In high occlusions it will be early and consist essentially of gastric juices. The presence or absence of bile (which is secreted at the level of the second duodenal portion) will help to further distinguish the level of obstruction.

In medium-low, intestinal and colic obstructions, vomiting will occur later, often taking on faecaloid connotations and becoming rarer or absent in rectal obstructions.

Vomiting is responsible, in the most severe cases, for hydro-electrolyte and acid-base imbalance

A) Alterations in alvus. One can find:

- diarrhoea: in some appendicitis and peritonitis

- stool and gas obstruction: in intestinal occlusions and some peritonitis

- melaena: in upper intestinal haemorrhages (stomach, duodenum, small intestine)

- rectorrhagia: in lower intestinal haemorrhages (colon and rectum)

B) Shock. It may occur during an acute abdominal picture triggered by particularly severe or untreated pathologies:

C) cardio-vascular such as myocardial infarction or intestinal infarction,

D) intra-abdominal haemorrhagic such as ruptured spleen or extra-uterine pregnancy

E) endo-luminal haemorrhagic due to gastro-duodenal, intestinal, colon bleeding

F) septic and toxic due to peritoneal reabsorption of certain substances: pus (infections), necrotic material (infections and tumours), enteric sewage (perforations).

Diagnosis of acute abdomen

The diagnosis of an acute abdomen, which is obvious in the presence of a clinical picture localised to the abdomen and characterised by painful symptoms, is only a starting point in a sometimes very complex pathway aimed at establishing

- whether the abdominal picture is of a medical or surgical nature and consequently the destination of the patient, who must be referred from the emergency room to the appropriate departments: general medicine, emergency surgery, coronary intensive care unit, vascular surgery

- whether the situation, in cases of surgical relevance, makes it possible to wait for the formulation of an aetiological diagnosis and thus to make a ‘targeted’ surgical indication, or rather requires an urgent and indefensible intervention that disregards the ascertainment of the triggering cause. This ‘generic’ surgical indication is usually used in the case of:

- endocavitary haemorrhage in progress: injury to parenchymatous organs spleen and liver, ectopic pregnancy

- perforation of hollow viscera: stomach, duodenum, intestines, bile ducts

- vascular distress of organs: strangulation of internal hernias, volvulus, formation of cicatricial bridles, intestinal infarction.

Although today, in most cases, it is instrumental and laboratory investigations that provide the decisive elements for diagnosis, classical semeiotics retains its importance.

It is from observing the patient and comparing the data it offers with those provided by instrumental investigations that the setting of a correct diagnostic pathway depends, the choice of urgent surgical treatment or the setting of certain pharmacological therapies that, when applied in a timely manner, can change the prognosis of serious diseases such as a heart attack or diabetic ketoacidosis.

Medical history

Anamnestic data can be collected directly from the patient or, in the event of his or her inability to render them, from family members or possible carers.

It provides important clues: a history of peptic disease will point towards a possible perforative complication, one of cardiac arrhythmia towards an intestinal infarction, a traumatic event will suggest injury to internal organs resulting in haemoperitoneum.

Physical examination

- Inspection of the patient: allows assessment of the patient’s complexion, appearance, decubitus, degree of distress.

During a biliary or renal colic the patient will appear restless and agitated, if in peritonitis he will show a very distressed face, the “peritonitis facies” and the characteristic position in lateral decubitus with the thighs flexed on the pelvis.

- Semeiotics of the abdomen.

- inspection: this is used to assess the degree of distension of the wall, the presence of any hernias, laparoceles or intestinal adhesions with scars from previous surgery that for various reasons cause intestinal obstruction.

- percussion: with which one can highlight areas of ‘obtuseness’ due to fluid spillage or ‘tympanism’ due to the presence of air, free in the cavity or sequestered in large quantities in the dilated intestinal loops due to occlusive phenomena.

- auscultation: useful in determining the presence and extent of intestinal peristalsis and any hydro-aerial noises.

- palpation: decisive in ascertaining

- the positivity of certain manoeuvres: Murphy’s sign, Blumberg’s sign, Rovsing’s sign,

- the painfulness of certain points: cystic, McBurney’s

- the onset of the contracture of the wall which becomes rigid, of ‘ligneous’ consistency and which represents an important sign of peritonitis.

5. Rectal exploration and gynaecological examination. With which a marked tenderness to pressure at the hollowing of the Douglas.

6. Detection: of the frequency and characteristics of the arterial pulse and respiration, blood pressure, body temperature.

Differential diagnosis

In the presence of an acute abdomen, a number of important decisions must be made, which generally occur in this order:

A) Establishing whether it is a true or false surgical abdominal picture, as is often called that resulting from diseases of internal medicine:

- Porphyria, Collagen diseases, Haemolytic crises, Diabetic ketoacidosis, Urological pathologies, Pulmonary infarction, Acute glissonian distension

B) In the context of pathologies of surgical interest, recognise situations requiring immediate intervention:

- Peritonitis in progress

from a phlogistic process affecting an organ: appendix, gallbladder, intestine, salpingi, etc.

from perforation of a hollow organ: stomach, duodenum, small intestine, colon, gallbladder, appendix…

- Endocavitary haemorrhage: rupture of spleen or liver, ectopic pregnancy…

- Vascular distress: intestinal infarction, hernial stricture, adhesional bridles

For the others decide ‘if’ and ‘when’ to intervene.

A surgical abdomen does not necessarily imply surgical treatment, or at least urgent treatment.

As a matter of principle, the use of elective surgical treatment is preferable to urgent treatment because it allows the surgery to be planned and therefore targeted laparatomies to be performed, but above all it allows patients to be adequately prepared.

Moreover, many pathologies, even serious ones, can resolve spontaneously or after medical therapy.

An emblematic case is that of appendicular pathology.

Appendicitis is one of the leading causes of surgical morbidity, has an unpredictable course, in many cases is difficult to diagnose, and requires careful diagnostic evaluation in a differential sense; ultimately, it requires vigilant waiting.

Differential diagnosis therefore has the most difficult task.

Fortunately, it can be aided by numerous instrumental investigations, in particular CT scans, and laboratory investigations, but certainly the basis of any decision remains the clinical observation of the patient because it allows one to grasp the moment when, as mentioned, an acute abdominal picture becomes a surgical abdominal emergency: when the contracture of the abdominal wall is present, there is no more time to discuss the temperature, which may be normal, to take a pulse ten times that seems reassuring, to rejoice because the vomiting has not worsened. The time for consultation and chatter has passed when, with all certainty, it is time for the scalpel.

General therapy for acute abdomen

Every acute abdomen must be treated, from the outset, with a series of measures aimed at preventing or correcting the hydro-electrolyte imbalances induced by diseases such as intestinal obstruction or vomiting and diarrhoea also associated with other diseases, at supporting cardiac activity and volaemia, and at providing adequate coverage with antibiotics.

Pain therapy deserves a separate discourse since, although it is appropriate and often unavoidable, it must be undertaken with the awareness that the administration of this type of drug can alter the type of pain and mask serious situations such as the onset of peritonitis.

Specific therapy

There are many medical conditions that can lead to an acute abdomen and each requires its own specific therapy.

With regard to surgical ones, a distinction must be made between ‘exploratory’ and ‘curative’ interventions.

The latter, aimed at controlling and eliminating the triggering cause, depend on the pathology in being: tumour, inflammatory, degenerative.

The so-called ‘exploratory’ laparotomy operations, however, are also intended to be curative.

In recent years, laparoscopic surgery has become increasingly important and is preferred by many surgeons to traditional open surgery.

In fact, although it is contraindicated or unsuitable in certain situations such as haemorrhagic or perforative states and in advanced occlusive states, it has many advantages:

- From a diagnostic point of view, it is the ideal solution because it allows the entire abdominal cavity to be explored using a minimal access route.

- Being minimally invasive, it has less impact on the patient’s general condition and avoids serious sequelae associated with traditional laparatomies such as laparocele.

- From a therapeutic point of view, it makes it possible to quickly resolve certain pathological situations such as the lysis of adhesions between the viscera or the removal of stenotizing bridges, and to adequately address many others.

When it proves to be insufficient or unsuitable, it can be quickly ‘converted’ to traditional laparatomy.

Read Also:

Emergency Live Even More…Live: Download The New Free App Of Your Newspaper For IOS And Android

What’s Causing Your Abdominal Pain And How To Treat It

Intestinal Infections: How Is Dientamoeba Fragilis Infection Contracted?

Early Parenteral Nutrition Support Cuts Infections After Major Abdominal Surgery