Basic airway assessment: an overview

The basic assessment of any patient, the “ABC’s” begins with the airway, a compromised airway is one of the quickest killers in all of medicine, making an accurate assessment a priority

This section will review the assessment of the unresponsive patient, the responsive patient, and several special situations that change typical management.

Airway assessment: the unresponsive patient

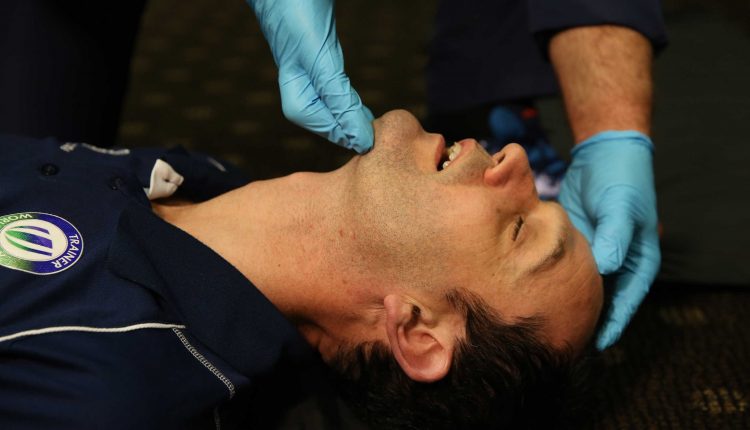

Unresponsive patients should have their airway opened and maintained manually.

Non-Traumatic mechanisms of injury should lead to the usage of the head-tilt and chin-lift technique.

While patients with Traumatic injuries that may compromise the C-spine are limited to the jaw-thrust technique.

This prevents the potential worsening of an unstable spinal injury.

If the airway cannot be maintained with a jaw thrust in a spinal trauma patient, it is appropriate to carefully perform the chin-lift maneuver and manually hold C-spine alignment with the head tilted.

This is allowed due to the patency of the airway being one of the key aspects of survival.

AIRWAY STATUS:

The only absolute indicator of airway status in unresponsive patients is the movement of air.

Seeing condensation in oxygen masks, feeling air movement, and using end-tidal CO2 monitors are all good ways of ensuring ventilation is occurring.

AIRWAY, DANGER SIGNS:

Snoring, gurgling, choking, and coughing are all potential indicators of compromised airways in unconscious patients.

If these are occurring it would be wise to reposition the patient or consider airway-related interventions.

Airway assessment: The Responsive Patient

The best sign of airway patency in responsive patients is the ability to hold a conversation without changes in the voice or feeling of breathlessness.

However, a patient’s airway may still be at risk even when they are conversational.

Foreign bodies or substances in the mouth may impair the airway at a later time and must be removed.

FOREIGN BODY REMOVAL:

Techniques to remove foreign bodies or substances are the finger sweep and suction.

The finger sweep is only used when a solid object is directly visualized and suction is used when liquids are seen or suspected.

Stridor is a common sign of airway narrowing, generally due to partial obstruction by a foreign body, swelling, or trauma.

It is defined as a high pitched whistling sound upon inspiration.

Respiratory Rate

The respiratory rate is a vital part of the primary survey.

While generally considered part of the “B” in “ABC’s” the respiratory rate is usually assessed at the same time as the airway

The normal adult resting respiratory rate is 12 to 20 breaths per minute (BPM).

Breathing too slow (bradypnea), too fast (tachypnea), or not at (apnea) all are commonly encountered conditions in the field.

BRADYPNEA:

A slow RR is generally the result of neurological compromise, since the RR is closely controlled by the hypothalamus this is generally the sign of a severe condition.

Suspect drug overdose, spinal injury, brain injury, or a severe medical condition when encountering a slow RR.

TACHYPNEA:

A fast RR is most often the result of physical exertion. Medical illness and airway obstruction are other common causes.

Tachypnea can lead to imbalances in the body’s acid-base status or exhaustion of the respiratory muscles.

APNEA:

An absence of breathing should be treated with a re-assessment of the airway followed by rapid initiation of mechanical ventilation, generally via bag valve mask.

Patients that are gasping occasionally should be treated as apneic until proven otherwise.

Airway Management

Breathing that is abnormal should be treated.

The definition of abnormal is broad, look for the following:

- Shallow chest rise and fall

- Noisy breathing (gurgling, wheezing, snoring)

- Difficulty breathing (use of the muscles in the neck/ribs/abdomen, nasal flaring, or tripod positioning.)

Management of abnormal breathing occurs in the following steps:

(In the majority of cases management will consist of regular re-assessments of the airway and administration of oxygen until transfer to a higher level of care.)

- opening the airway

- assessing for patency (airflow and presence of obstruction)

- administering oxygen via nasal cannula or mask

Assisting breathing with a BVM if the patient is unresponsive or if the skin is blue (cyanotic)

Special Populations

Pediatric patients and geriatric patients have different demands for oxygen when compared to average middle-aged adults.

This leads to differences in normal values for respiration rate, depth, and quality.

PEDIATRIC:

Pediatric patients breathe much faster than middle-aged adults but have less volume to each breath.

The exact expected respiratory rate varies significantly with age.

Know that newborns should be at 30 to 50 bpm, and children one-month-old to 12 years old should be between 30 and 20.

Pediatric patients with abnormal breathing can rapidly decompensate and become life-threateningly unstable with little warning.

GERIATRIC:

Geriatric patients commonly have an increased need for oxygen given naturally declining lung function and the common presence of underlying medical issues.

This leads to a wide normal range.

Healthy elderly patients should be at a rate of 12 to 18, while unhealthy patients can be as high as 25 and still be considered normal if otherwise asymptomatic.

Like pediatric patients, an elderly patient with abnormal breathing can rapidly decompensate even if seemingly stable.

AIRWAY MANAGEMENT DURING PREGNANCY:

Pregnancy makes breathing more difficult.

The increased upward pressure from the growing fetus restricts the downward movement of the diaphragm, naturally, the difficulty of breathing increases the further along the woman is in pregnancy.

In the third trimester, many women make increased use of the accessory muscles which can cause costochondritis.

Recumbent (lying or reclining) positions worsen pregnancy-related breathing difficulty.

Dyspnea due to pregnancy can likewise be relieved by sitting the patient up or elevating the head-of-bed to a 45° or greater angle.

Patients with twins or triplets may require supplemental oxygen due to the significant growth of the uterus.

This can occur as early as the second trimester.

Read Also:

Emergency Live Even More…Live: Download The New Free App Of Your Newspaper For IOS And Android

Airway Management After A Road Accident: An Overview

Tracheal Intubation: When, How And Why To Create An Artificial Airway For The Patient

What Is Transient Tachypnoea Of The Newborn, Or Neonatal Wet Lung Syndrome?

Traumatic Pneumothorax: Symptoms, Diagnosis And Treatment

Diagnosis Of Tension Pneumothorax In The Field: Suction Or Blowing?

Pneumothorax And Pneumomediastinum: Rescuing The Patient With Pulmonary Barotrauma

ABC, ABCD And ABCDE Rule In Emergency Medicine: What The Rescuer Must Do

Multiple Rib Fracture, Flail Chest (Rib Volet) And Pneumothorax: An Overview

Internal Haemorrhage: Definition, Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis, Severity, Treatment

Cervical Collar In Trauma Patients In Emergency Medicine: When To Use It, Why It Is Important

KED Extrication Device For Trauma Extraction: What It Is And How To Use It

How Is Triage Carried Out In The Emergency Department? The START And CESIRA Methods

Chest Trauma: Clinical Aspects, Therapy, Airway And Ventilatory Assistance