Peptic ulcer, symptoms and diagnosis

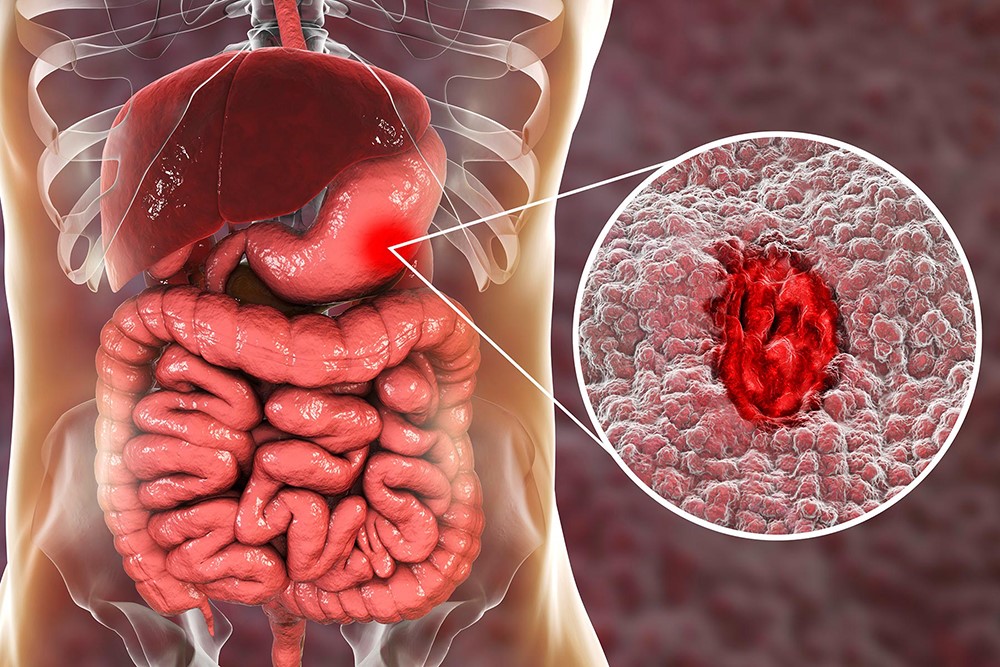

A peptic ulcer is a wound (from ‘ulcus’ = ulcer), a lesion of the inner wall of the digestive canal, of its inner lining

It appears as a continuous solution of the mucosa with more or less extensive loss of substance; loss that from the superficial plane of the mucosa goes beyond the level of the muscolaris mucosa, sometimes extending even further into the wall of the digestive tract and reaching the submucosa and muscolaris propria.

It is also called ‘peptic’ (from ‘peptikòs’ = digestive) in analogy to ‘pepsin’, an enzyme substance whose action plays an important role in digestion and, in certain cases, in the determinism of the disease.

A more superficial lesion, which does not reach the muscolaris mucosa, is called erosion.

Peptic ulcer can affect different tracts of the digestive system such as oesophagus, stomach, duodenum, anastomosed loop in gastroresectees, Meckel’s diverticulum in the small intestine

It has a multifactorial aetiology and forms as a result of an imbalance between ‘aggressive’ and ‘protective’ factors of the mucosa.

Aggressive factors are pepsin and hydrochloric acid, normally present in varying amounts and proportions in gastric juice, while protective factors are represented essentially by the mucosal barrier, a protective barrier consisting of mucus, bicarbonates and good normal tissue blood supply.

But an important role in the pathogenetic mechanism of the ulcer we know is often played by infection with Helicobacter pylori (H.P., formerly called Campylobacter pylori), a germ whose discovery has opened up completely new horizons in the etiopathogenesis and therapy of ulcers.

The discovery of the micro-organism revolutionised therapy, leading to a sharp drop in ulcer patients over the last 30 years, especially duodenal ulcer patients, and drastically reducing the number of surgeries and gastroresections (Billroth II) for ulcers.

Most probably, the disease also depends on the interaction between the genetic virulence factors of the H.P. strain (CagA, VacA) and the genetic predisposition of the host subject (group 0, for instance, seems to be more predisposed as some HLA haplotypes), as well as other environmental, dietary and/or toxic factors (e.g. smoking, caffeine, gastrolesive substances, stress, etc.) characteristic of the subject itself.

But, mind you, peptic, gastric or duodenal ulcers can appear even in the absence of H.P. infection:

In fact, one speaks of an H.P positive or H.P negative ulcer depending on the presence or absence of Helicobacter Pylori.

It should also be pointed out that the presence of Helicobacter Pylori in the stomach always leads to a chronic disease, chronic gastritis, which can go on for a long time even asymptomatically (even for life) and which only in a certain percentage of cases can lead to a peptic ulcer (about 15-20% of cases), but that about 80% of ulcers have H. P. infection. P. and that gastric ulcer represents the most important risk factor for gastric adenocarcinoma.

P. infection is in fact the leading cause of peptic, gastric and duodenal ulcer, gastric MALT lymphoma and gastric cancer.

Not all H.P. infections, however, lead to peptic ulcer, but only in 10-20% of infected individuals.

Peptic ulcer should therefore be more correctly treated within the more general framework of gastropathies

Gastropathies can be acute or chronic, from Helicobacter pylori and related pathology or from drugs such as jatrogenic or stress gastritis, or from other factors and gastrolesive agents (alcohol, tobacco smoke, caffeine, CMV cytomegalovirus, rotavirus, etc.).

The above-mentioned genetic factors would significantly affect the evolution of chronic gastritis, inactive or active, into atrophic and metaplasia, and the onset of a gastric or duodenal ulcer, or its complications.

Complications may also include the various forms of benign or malignant neoplasia (e.g. lymphoma, adenoma, GIST, gastric adenocarcinoma), the latter being almost exclusively confined to the stomach.

In particular, gastric ulcer appears to recognise cigarette smoking and alcohol as major risk factors, whereas in duodenal ulcer the predominant risk factor is H.P.

Epidemiology

Ten per cent of the population suffers from peptic ulcers during their lifetime.

According to the latest data, gastric ulcer currently affects 2.5% of the population, but the percentage is twice as high in men as in women; duodenal ulcer affects about 1.8%, predominantly younger people.

Of those infected with H.P., only about 20% get peptic ulcers.

But 80% of ulcers are caused by H.P. and 20-30% of the population in the West is H.P. infected.

In developing countries, however, a large part of the population is infected with H.P., at least up to 70%.

Hence the importance and role of H.P. in the cause and spread of peptic ulcer and consequently the importance of its eradication in peptic ulcer therapy, as well as in the prevention of chronic gastritis and stomach cancer.

The other frequent cause of ulcers is the intake of anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), the many other drugs and gastrolesting agents, and stress (including surgical stress). Twenty-five per cent of those taking NSAIDs (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) present with ulcers on endoscopic examination, but most remain clinically silent.

The patients most at risk are the elderly and the chronically ill who take gastrolesive drugs for long periods (fans, cortisone, anticoagulants, aspirin even at low doses) who should therefore receive gastroprotectors at the same time.

It is estimated that the most alarming acute complication of ulcers – digestive bleeding, which involves a mortality of 10 per cent – affects a quarter of elderly people who use NSAIDs.

What are the symptoms of peptic ulcer

Characteristic symptoms of an ulcer are burning and/or pain in the epigastrium (the epigastrium is the upper and middle part of the abdomen), which is particularly intense in the early hours of the night and subsides with the ingestion of food.

The pain, especially when intense, may radiate posteriorly to the chest.

These symptoms may be associated with epigastric weight sensation after eating (dyspepsia), nausea and/or vomiting.

It is not uncommon for the ulcer to manifest itself atypically with vague abdominal pain or even to cause no symptoms at all.

Ulcer pain is aggravated by pressure on the epigastrium.

This finding is important in that it helps to distinguish it from cardiac pain, which may be localised “in the stomach” but which is not affected by deep palpation of the epigastrium, and which in any case should always be adequately excluded at the time of first intervention.

The symptoms of peptic ulcer are different depending on whether it is a gastric or duodenal ulcer

Epigastric pain is common to both, but sometimes there is no or only minor symptoms, such as vague dyspepsia or aerogastria or a sense of postprandial stuffiness.

In some cases, however, the peptic ulcer may be asymptomatic and perhaps present suddenly with a haemorrhage or other complication.

The oesophageal ulcer would then deserve a separate treatment because of the particularity of its mechanisms of onset and treatment, as it is often linked to the presence of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease.

The duodenal ulcer mostly presents with aching pain and hyperacidity, heartburn, usually some time after the meal (2-3 hours), nausea, aerogastria, halitosis; often the pain subsides or is relieved by the ingestion of milk or food; sometimes the epigastric pain occurs on an empty stomach and/or during the night.

In gastric ulcers, the symptoms are deep, dull epigastric pain, sometimes radiating posteriorly to the back, a pain that arises early, immediately after a meal or even exacerbated by the meal, lack of appetite, a sense of fullness, anaemia, nausea and vomiting; the ingestion of food does not bring relief.

The natural history of an ulcer is that of a disease that tends, especially if insufficiently or inadequately treated, to recur over time with periods of seasonal flare-ups or to complicate suddenly with possible and difficult emergencies.

A quarter of patients experience severe complications, acute events such as haemorrhage (15-20 %) and/or perforation (2-10 %), such as stenosis due to a fibrocystic outcome or perforation and inflammatory and necrotic involvement of the pancreas.

In some individuals, especially if not eradicated of H.P., or reinfected, multiple ulcerations or episodes of ulcer recurrence or repeated complications may develop as in Zollinger-Ellison syndrome or Gastrinoma.

In this regard, it is worth pointing out the importance of a still little known and used test such as the Gastropanel, which can detect the presence of an excess of acid hypersecretion, antral G-cell hypertrophy or hypogastrinemia, as well as the possible existence of a risk terrain for ulcer and for neoplasms such as chronic gastritis or mucous membrane atrophy, in all or certain parts of the stomach.

What tests to do to diagnose peptic ulcer

Until a few years ago, in the pre-endoscopic era, the main examination to diagnose an ulcer was the X-ray examination with baryta meal.

Nowadays, the main examination to diagnose an ulcer with certainty is fibre-optic endoscopy (oesophago-gastro-duodenoscopy or EGDscopy).

It is a simple and non-risky investigation that also allows small sampling of the mucosa to search for the presence of Helicobacter Pylori or to rule out the presence of a tumour (necessary in the case of a gastric ulcer) or for diagnosing chronic gastritis. But radiology is not supplanted, it remains useful and in some cases necessary.

The endoscopic examination has a 95-100% sensitivity of detecting ulcer pathology and also allows possible biopsies or emergency treatment, such as in haemorrhage.

Endoscopy is also important in recognising, classifying and monitoring cases of chronic gastritis and mucosal atrophy.

In addition, in particularly well-equipped centres, Oesophagogastroduodenoscopy today also allows for the more accurate diagnosis of possibly associated or suspected pathologies, by means of innovative methods such as chromoendoscopy with the use of vital staining.

Endoscopy is necessary in patients over 45 years of age in order to rule out the presence of a tumour.

In younger patients, especially those with typical symptoms, a test for Helicobacter Pylori alone can also be performed: if it is positive, the presence of an ulcer is more likely.

The search for the bacterium can be carried out with various tests, invasive tests (rapid urease test, histological examination and culture test) and non-invasive tests (C-urea Breath test, stool test and serology).

The best known is the labelled urea breath test (Urea Breath Test).

To perform this test, the patient must drink a liquid containing urea labelled with a non-radioactive carbon isotope [C13] and then blow at different times into a test tube.

The presence of infection is established by measuring the concentration of C13 in the air emitted with the breath.

Another widely used test is the anti-Helicobacter Pylori antibody test, which is usually performed on blood, but has the disadvantage that it does not distinguish an ongoing infection from a previous one.

In contrast, the search for H.P. antigen in faeces is much more useful and reliable, and can also be performed on saliva or faeces.

It should be noted that H.P. antigen detection in faeces has a sensitivity and specificity of over 95%, which is therefore comparable to the urea breath test and superior to the more invasive, perendoscopic, rapid urease test, which does not exceed 90-95%.

Only the cultural test, which is invasive and rarely used, is of higher reliability and could reach 99%.

But it is reserved for a few special cases.

Worth mentioning, once again, is the Gastropanel, the diagnostic laboratory investigation of the state of the gastric mucosa, which detects the dosage of pepsinogen I and pepsinogen II and their ratio, gastrinemia and anti-H.P. antibodies in the blood.

What are the stages of peptic ulcer

Peptic ulcer is a relapsing disease, with characteristic flare-ups at the change of season and especially during stress. Correct treatment can reduce the tendency for the disease to recur.

In the absence of adequate treatment, complications may arise that can be classified as follows

- haemorrhage: the ulcer can erode blood vessels and cause haemorrhaging, which is manifested by the emission of pitch-black stools (melena) or by dark, ‘coffee-coloured’ vomiting or haematemesis (haematemesis);

- perforation: occurs when the ulcer involves the entire thickness of the gastric or duodenal wall and opens into the peritoneal cavity. This is immediately followed by acute inflammation of the peritoneum (peritonitis) which manifests itself with violent abdominal pain and intestinal obstruction;

- penetration: this occurs when the ulcerating process, having passed the intestinal wall, penetrates a neighbouring organ (most frequently the pancreas);

- pyloric stenosis: an ulcer located at the end of the stomach or in the channel that connects the stomach and duodenum (pylorus) can lead to a narrowing of this channel resulting in an inability to empty the stomach (gastric stagnation);

- cancer of gastric ulcer.

Peptic ulcer: some advice

If a peptic ulcer has been diagnosed, it is important to know a few basics.

It is not necessary to follow a particular diet (the so-called ‘blank diet’ that was once frequently recommended is useless); it is enough to eat a healthy, balanced diet and to observe regular meal rhythms and times.

Furthermore:

- it is definitely harmful to smoke cigarettes, as it reduces the likelihood of ulcer healing; it further damages the gastric mucosa and adversely affects the cardia and the tone of the lower oesophageal sphincter.

- Avoid or limit the consumption of alcohol and stimulating beverages such as coffee, tea, cola; avoid carbonated water, copious meals and certain foods such as meat broth, pepper sauces, tomatoes, sauces cooked in oil or butter or margarine, citrus fruits, refined sweets, too much chocolate, mint, spicy foods, cold cuts and sausages, fried foods, boiled or overcooked meats, canned tuna, dried fruits. On the other hand, liquorice, lean meat, bananas, garlic, cabbage, non-acidic, fresh or cooked fruit, for some also spices and chilli peppers, bread on toast or without crumbs, yoghurt, fresh fish, cold cuts, cheese and grana padano cheese are useful. In moderation, wine, mint, citrus fruits, peppers, skimmed milk, pepper; pasta, rice, potatoes, ripe fruit and seasonal vegetables are permitted.

- The intake of gastrolesive drugs (such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, cortisone, etc.) must be avoided at all costs, as they can aggravate the ulcerative process, leading to complications (especially haemorrhaging); if they are absolutely necessary, use gastroprotectors.

- Appropriate therapy should be scrupulously followed.

- Undergo Helicobacter Pylori testing until it has been eradicated.

- Avoid stressful occasions.

- Consult your doctor periodically and take advantage of the expertise of your gastroenterologist.

Therapeutic approaches to peptic ulcers

Medical therapy is based on the use of various drugs. Firstly, antisecretory drugs that block the production of gastric acid.

These drugs are the anti-H2 drugs (such as ranitidine), now almost entirely supplanted by the newer, more effective proton pump inhibitors PPIs (lansoprazole, omeprazole, pantoprazole, esomeprazole, etc.).

When the peptic ulcer is caused, as is often the case, by a Helicobacter Pylori infection, PPIs are combined with certain antibiotics in combination (e.g. amoxicillin + clarithromycin + PPIs) or other substances depending on the protocols adopted, for a short and limited period of time, to eradicate the infection.

It sometimes happens, however, that the eradication attempt fails and the infection persists, due to resistance to the antibiotics used, resistance most frequently found to be to clarithromycin.

In such cases, it is necessary to switch to other combinations (in triple therapy’) of antibiotics: amoxicillin + metronidazole or (or later) levofloxacin + amoxicillin; or concomitant therapy with clarithromycin + metronidazole + amoxicillin.

The most recent composition proposed, in quadruple therapy, consists (also included in a single commercial package) of bismuth subcitrate potassium + amoxicillin + tetracycline, always associated with proton pump inhibitors (PPIs).

The therapy thus indicated should be continued for 10-14 days. After that, PPI therapy alone is continued.

It is of course important to ascertain whether eradication has taken place by means of the appropriate laboratory investigation

If eradication has been successful, PPI therapy is usually continued for a limited period of time, longer or shorter depending on the case, until the clinical condition stabilises.

Long-term therapy almost as a rule, which has been used in the past, is no longer used, except in special cases as judged by the doctor.

In addition to the above-mentioned medicines there are many other molecules and pharmaceutical products whose use is frequently found in medical practice, either to supplement the above-mentioned therapies or to deal with particular organic or functional disorders associated with ulcerative disease.

Antacids, of which there are many varieties (e.g. aluminium hydroxide and magnesium hydroxide) can be combined as symptomatic agents to temporarily buffer acidity, and mucosal protectors to hinder acid damage and promote ulcer healing; magaldrate, sodium alginate and magnesium alginate, potassium bicarbonate.

Other molecules useful and often used in the treatment of ulcers, in their possible and various clinical presentations and symptomatic aspects, are sucralfate for its protective and repairing action on the mucosa, as well as misoprostol as a cytoprotective agent or colloidal bismuth or hyaluronic acid and hydrolysed keratin, prokinetics such as levosulpiride or domperidone to favour gastric emptying, anti-meteoric agents against meteorism.

Finally, probiotics are promising according to the latest views, with interesting therapeutic prospects.

In the presence of ‘alarm’ symptoms such as melena or haematemesis, immediate hospitalisation is important.

Surgical therapy, which was widely used in the past, is now only indicated for the treatment of serious complications which otherwise cannot be overcome (perforation, pyloric stenosis, haemorrhage which cannot be controlled by medical or endoscopic therapy).

Of course, early gastric cancer, or initial cancer, and in any case the chancellisation of an ulcer require a decisive, timely and appropriate surgical solution.

Read Also:

Emergency Live Even More…Live: Download The New Free App Of Your Newspaper For IOS And Android

Peptic Ulcer, Often Caused By Helicobacter Pylori

Peptic Ulcer: The Differences Between Gastric Ulcer And Duodenal Ulcer

Wales’ Bowel Surgery Death Rate ‘Higher Than Expected’

Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS): A Benign Condition To Keep Under Control

Ulcerative Colitis: Is There A Cure?

Colitis And Irritable Bowel Syndrome: What Is The Difference And How To Distinguish Between Them?

Irritable Bowel Syndrome: The Symptoms It Can Manifest Itself With

Can Stress Cause A Peptic Ulcer?