Alzheimer's disease, symptoms and diagnosis

Alzheimer’s disease is the most frequent variety of primary dementia in the world. Alzheimer’s disease gradually presents with memory loss, difficulty in movement, loss of language ability, and difficulty recognizing objects and people

Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s is difficult because these symptoms are confused with those typical of other forms of dementia.

Symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease

Typical symptoms of Alzheimer’s occur gradually over the course of the disease and include:

- Memory loss;

- Spatiotemporal disorientation;

- Mood alterations;

- Personality changes;

- Agnosia i.e. difficulty in object recognition;

- Aphasia i.e. loss of language skills;

- Apraxia i.e., inability to move and coordinate;

- Communication difficulties;

- Aggressiveness;

- Physical changes.

What is meant by dementia

Dementia is defined as the more or less rapid loss of upper cortical functions.

Higher cortical functions are divided into four broad categories: phasia, praxia, gnosia, and mnesia.

- Fasia is the ability to communicate through linguistic coding, whether written or spoken;

- praxia is the ability to direct voluntary body movements in relation to a project (transitive praxia) or a gestural communicative instance (intransitive praxia);

- gnosia is the ability to attribute meaning to stimuli from the surrounding world and/or one’s own body;

- mnesia is the ability to acquire news from interactions with the world and to be able to recall it later according to a correct chronology.

These four functions, which are actually very much embriched with each other (think, for example, of how much the expression of written language depends on the integrity of the appropriate motor patterns for physically enacting it, or how much the ability to remember facts or objects is linked to the ability to grasp their correct meaning), are the target of diseases characterized by dementia, such as Alzheimer’s.

There are other important categories that can be directly ascribed to the functionality of the cerebral cortex, such as judgment, mood, empathy, and the ability to maintain a constant linearity of the flow of ideas (i.e., attention), but disorders that electively affect these other functions are, more or less legitimately, made to fall under the umbrella of psychiatric disorders.

Dementia between psychiatry and neurology

As we shall see later, this separation between specialized fields (neurology and psychiatry) does not help in the correct understanding of the demented patient (and therefore the Alzheimer’s patient), who in fact presents almost constantly the impairment of all the aforementioned cognitive spheres, albeit with variable prevalence of one or the other.

What currently continues to separate the two branches of medical knowledge (in fact until the 1970s integrated into the single discipline “neuropsychiatry”) is the failure to find a clear macro- and microscopic biological pattern in “purely” psychiatric diseases.

Thus, dementia is the result of an anatomically detectable process of degeneration of the cells of the cerebral cortex assigned to cognitive functions.

Therefore, those conditions of brain suffering that impair the state of consciousness should be excluded in the definition: the dementia patient is alert.

Primary dementia and secondary dementia

Having ascertained the condition of dementia, the further important distinction arises between secondary forms due to brain damage caused by disorders in non-nerve structures (first of all the vascular tree, then the meningeal linings, then the supporting connective cells), secondary forms due to nerve damage elicited by known causative agents (infections, toxic substances, abnormal activation of inflammation, genetic errors, trauma), and finally to nerve cell damage without known causes, i.e., “primary.”

The phenomenon of primary neuronal damage that selectively affects nerve cells in the cerebral cortex used for cognitive functions (also called “associative cortex”) represents the true pathological substrate of what we call Alzheimer’s Disease.

Graduality of symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease

Alzheimer’s dementia is a chronic degenerative disease, the insidiousness of which is so well known to the general public that it is one of the most frequent fears that prompt patients, especially after a certain age, to seek a neurological examination.

The biological reason for this gradual progression of symptoms at the onset of Alzheimer’s disease is inherent in the concept of “functional reserve”: the compensatory capacities offered by a system characterized by a wide redundancy of connections, as the brain is, allows the latter to succeed in ensuring the maintenance of functional capacities up to a minimum numerical term of cell population, beyond which appears the loss of function whose decay assumes a catastrophic progression from that moment on.

To conceive of such a progression, one must then imagine that the microscopic disease is gradually established several years before its clinical manifestation, the course of which will be all the more rapidly devastating the earlier the process of silent cell death had manifested.

The stages of Alzheimer’s disease and related symptoms

Having clarified this temporal dynamic, it becomes easier to interpret the symptoms that mark the disease’s, alas relentless, course: scholastically, we distinguish a psychiatric phase, a neurological phase, and an internalized, terminal phase of the disease.

The entire clinical course is staggered over an average period of 8 to 15 years, with wide interindividual variations related to several factors, chief among them the degree of mental exercise the patient has maintained throughout his or her life, which is recognized as the main factor favoring prolongation of disease duration.

Stage 1. The psychiatric phase

The psychiatric phase is, from the point of view of the patient’s subjective well-being, basically the most distressing period.

He begins to feel his own loss of reliability with respect to himself and others; he is conscious of making mistakes in the performance of tasks and conduct to which he normally paid almost no attention: the choice of the most appropriate word in the expression of a thought, the best strategy for reaching a destination while driving a motor vehicle, the correct recollection of the succession of events that motivated a striking episode.

The patient distressingly feels the objective losses of ability, but these are so sporadic and heterogeneous that they do not provide him with logical explanations.

He fears manifesting his shortcomings, so he constantly tries to hide them from the public as well as from himself.

This state of psycho-emotional stress leads each alzheimer’s patient to assume different behavioral attitudes, depending on his or her personality traits:

- those who become intolerant and even aggressive toward any manifestation of attention from their relatives;

- those who close themselves off in a mutacism that soon takes on characteristics indistinguishable from a depressive mood state (they often receive prescriptions for antidepressant drugs at this stage);

- those who dissimulate by flaunting their hitherto intact communication skills, becoming facetious or even fatuous.

This marked variability certainly delays the diagnostic framing of the disease, even to experienced eyes.

We will see later how early diagnosis of the disease is unfortunately not decisive in influencing the natural history of the disease as much as it is essential to preserve as much as possible the integrity of the quality of life of patients’ families.

Phase 2. Neurological Phase

In the second, neurological phase, the deficits in the four upper cortical functions enunciated above clearly appear.

There seems to be no rule, but in most cases the first functions to be impaired seem to be the gnosic-attentive ones.

The perception of one’s self, both on the plane of one’s bodily integrity and on the plane of the architectural arrangement of the surrounding world, begins to falter causing on the one hand a diminished ability to sense one’s own state of pathology (anosognosia, a fact that partly frees the patient from the state of distress predominant in the previous phase), and on the other hand to place events correctly in the correct spatiotemporal arrangement.

Typically, the subject reveals an inability to retrace a route already taken having in mind the layout of the roads just crossed.

These manifestations, which are, moreover, common in nondemented persons as a result of trivial distractions, are often interpreted as “memory loss.”

It is important to establish the extent and persistence of the episodes of memory loss, because the actual mnestic deficit may on the other hand be a benign manifestation of the normal aging process in the elderly brain (the typical deficit of short-term mnestic reenactment being compensated for by the accentuation of events that took place many years earlier, the latter often enriched with details that actually happened).

The subsequent complete spatiotemporal disorientation begins to be associated with dispersive phenomena, sometimes with the character of true visual and auditory hallucinations and often with terrifying content.

The patient begins to reverse the sleep-wake rhythm, alternating long phases of alert inertia with bursts of restlessness, sometimes aggressive.

The disavowal of his surroundings leads him to react with astonishment and suspicion to hitherto familiar situations, the ability to acquire new events is lost structuring a complete “anterograde” amnesia that permanently impairs the ability to attribute meaning to one’s experience.

At the same time the usual gestural attitudes are lost, facial expressions and posture become incapable of expressing shared messages, the patient first loses constructive skills that require motor planning (e.g., cooking), then also motor sequences that are carried out with relative automaticity (clothing apraxia, to the loss of autonomy related to personal hygiene).

Phasic impairment involves both components that are classically distinguished in neurological semeiotics, i.e., the “motor” and the “sensory” components: in fact, there is both a clear lexical impoverishment, with numerous errors in the motor expression of sentences, and an increase in spontaneous fluency of speech that gradually loses meaning for the patient himself: the result is often a motor stereotypy in which the patient repeatedly declaims a more or less simple sentence, usually badly pronounced, completely afinalistic and indifferent to the interlocutor’s reaction.

The last function that is lost is that of recognition of family members, the later the closer they have been.

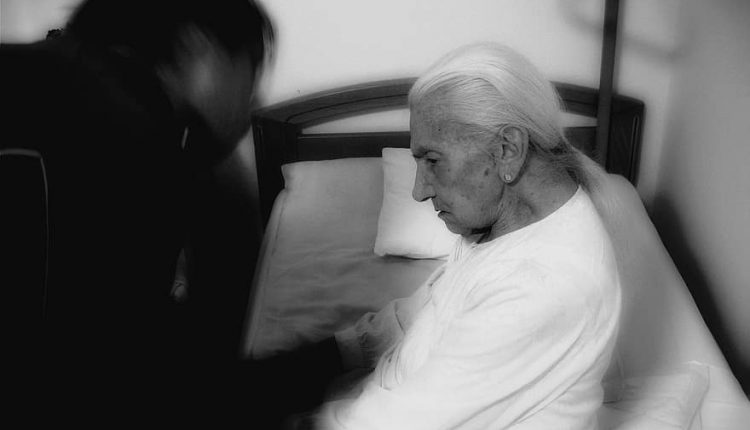

This is the most distressing phase for the patient’s relatives: behind the features of their loved one, an unknown being has progressively been substituted, which has moreover become more burdensome on the care plan every day.

It is no exaggeration to say that by the end of the neurological phase the object of medical care has gradually been passed on from the patient to his or her immediate family.

Stage 3. The internist phase

The internist phase sees a subject now devoid of motor initiative and intentionality of actions.

Vital automatisms have become enclosed in the immediate feeding and excretory spheres, often overlapping each other (coprophagia).

The patient also often carries organ disease related to the toxicity of medications that were necessarily taken to control the behavioral excesses of earlier stages of illness (neuroleptics, mood stabilizers, ect).

Beyond the specific conditions of hygiene and care in which each patient may find themselves, most of them are overwhelmed by intercurrent infections, the lethality of which seems particularly favored by the conditions of psycho-motor decline; others are seized by heart attack, many die from incoordination of swallowing (pneumonia ab ingestis).

Stage 4. The Terminal Phase

The slowly degenerative terminal stages are characterized by malnutrition to the point of cachexia and multiorgan pathology to complete marasmus of vegetative functions.

Unfortunately, but understandably, the patient’s death is often experienced by family members with a subtle vein of relief, the greater the longer the course of the disease has been.

Alzheimer’s disease: the causes

The causes of Alzheimer’s Disease are unknown to date.

The same cannot be said about the biomolecular knowledge and pathogenetic processes that have been progressively elucidated over the past 50 years of research.

Indeed, understanding what happens to the nerve cell affected by the disease does not necessarily mean identifying that particular event that triggers the pathological process, an event whose elimination or correction could allow the disease to be cured.

We now know with certainty that, as with other primary degenerative diseases of the central nervous system such as Parkinson’s disease and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, the underlying pathological mechanism is apoptosis, that is, a dysfunction of the mechanisms that regulate so-called “programmed cell death.”

We know that each type of cell in the body is characterized by a cycle in which a replication phase (mitosis) and a phase of metabolic activity alternate, which is specific to cell type (e.g., the biochemical activity of the liver cell versus the secretory activity of the intestinal epithelium cell).

The reciprocal amount of these two phases is not only cell type-specific but also varies along the differentiation process of cell lines from embryonic life to birth.

Thus, the embryonic precursors of neurons (neuroblasts) replicate very rapidly during the embryonic development of the brain, each reaching a maturity that coincides with the first few months after birth, at which time the cell becomes “perennial, that is, it no longer replicates until death.

The phenomenon predicts that mature nerve cells tend to die earlier than the subject’s expected lifespan, so that in old age the number of cells still alive is greatly reduced from the initial number.

Cell death, which occurs by a mechanism of active “killing” by the organism, precisely “programmed,” corresponds to a greater consolidation of connections already initiated by surviving cells.

This active process, called apoptosis, is one of the most important morpho-dynamic substrates of brain learning processes, as well as of the global phenomenon of aging.

On the bio-molecular details involved in this complex phenomenon of neuron life we now have an impressive amount of data and clarification.

What is still unclear is what mechanism governs the activation of apoptosis in normal cells and, more importantly, for what particular event in Alzheimer’s Disease apoptosis is activated to such a tumultuous and uncontrolled extent.

Epidemiology of Alzheimer’s disease

It has been mentioned that Alzheimer’s Disease, if properly diagnosed, rises to the top of the world’s most frequent primary neurodegenerative disease.

Since the socio-health motivations driving epidemiological research refer mainly to the disabling effects of various diseases, the most relevant statistics refer to the psycho-organic syndrome as a whole, i.e., dementia in general.

In European countries there are currently an estimated 15 million people with dementia.

Studies that analyze Alzheimer’s Disease in more detail quantify the latter at 54% compared to all other causes of dementia.

The incidence rates (number of newly diagnosed cases per year) are markedly variable according to the two seemingly most incisive parameters, namely age and sex: two age groups have been broken down, 65 to 69 and 69 and over.

The incidence can be expressed as the number of new cases out of the total number of individuals (made 1000) at risk of being affected in a year (1000 person-years): among males in the 65 to 69 age group, Alzheimer’s disease is 0.9 1000 person-years, in the later group it is 20 1000 person-years.

Among females, on the other hand, the increase ranges from 2.2 in the 65-69 age group to 69.7 cases per 1,000 person-years in the >90 years age group.

Diagnosing Alzheimer’s disease

The diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease comes through the clinical finding of dementia.

The pattern and succession of symptoms described above is in reality highly variable and inconstant.

It often happens that a patient described by family members as perfectly lucid and communicative until a few days before arrives for observation in the emergency room because during the night he went out on the street in a state of complete mental confusion.

The degenerative process that affects the cerebral cortex in the course of Alzheimer’s Disease is certainly a widespread and global phenomenon, but its progression can, as in all pathological phenomena, manifest itself with extreme topographical variability, so much so that it simulates pathological events of a focal nature, as happens, for example, in the course of arterial occlusion ischemia.

It is precisely with respect to this kind of pathology, namely multiinfarct vascular encephalopathy, that the physician must initially try to guide the correct diagnosis.

The hygienic, dietary and lifestyle conditions in the civilized world have certainly and heavily affected the epidemiology of diseases and, to a striking extent, have increased chronic obstructive vascular disease in the population in direct correlation with the increasingly advanced life expectancy.

Whereas, for example, in the 1920s, chronic degenerative diseases saw infectious diseases (tuberculosis, syphilis) as major players, today nosological phenomena such as hypertension and diabetes are explicitly spoken of in terms of endemics with epidemic progression.

Finding in a subject over 70 years of age a brain MRI completely free of signs of previous and multiple ischemia is in fact a (pleasant) exception.

The confounding element is inherent in the fact that, on the one hand as mentioned above Alzheimer’s Disease may initially have a seemingly multifocal course, on the other hand a progressive summation of point ischemic events in the brain will tend to produce dementia almost indistinguishable from Alzheimer’s Disease.

Added to this is the fact that there is no reason to rule out the concomitance of the two diseases.

An important discriminative criterion, in addition to that derived from neuroimaging examinations, is known to be supported by the presence, in multi-infarct dementias, of early involvement of movements, which may take on features of spastic paresis, disorders similar to those found in Parkinson’s disease (“extrapyramidal syndrome”) or have quite peculiar features, although not directly diagnostic, such as the so-called “pseudobulbar syndrome” (loss of the ability to articulate words, difficulty of swallowing food, emotional disinhibition, with unmotivated outbursts of crying or laughter) or the phenomenon of “marching in step” that precedes the initiation of walking.

A perhaps more incisive criterion, which nevertheless requires good information-gathering skills, lies in the time course of the disorders; whereas in Alzheimer’s Disease, although variable and inconstant, there is a certain gradualness in the worsening of cognitive functions, the course of multi-infarct dementias is characterized by a “stepped” course, that is, severe worsening of both mental and physical conditions interspersed with periods of relative stability of the clinical picture.

If it were a matter of having to distinguish only between these two pathological entities, however much they together account for almost all cases, the diagnostic task would be all in all easy: on the other hand, there are numerous pathological conditions that, although isolated in rare occurrence, must be taken into account because they carry both dementia and associated movement disorders.

To make a list of all these variants of dementia is beyond the scope of this brief talk; I mention here only the less relatively rare diseases such as Huntington’s chorea, progressive supranuclear palsy, and corticobasal degeneration.

The admixture of extrapyramidal movement disorders and psycho-cognitive impairment is also characteristic of several other diseases, more “related” to Parkinson’s disease, such as Lewy body dementia.

The clinical or, as is often the case, post-mortem possibility of formulating the diagnosis of other degenerative diseases in addition to Alzheimer’s Disease unfortunately does not affect the efficacy of available state-of-the-art therapies.

These are strictly neurological insights that assume at the most importance on the cognitive and epidemiological level.

Instead, a very important differential diagnosis for the patient is primary CSF hypertension also known as “normotensive hydrocephalus of the elderly.”

This is a chronic condition, induced by a defect in the secretion-reabsorption dynamics of cerebral CSF, progressively worsening, in which movement disorders, mostly extrapyramidal, are associated with cognitive deficits sometimes indistinguishable from the initial manifestations of Alzheimer’s disease.

The diagnostic relevance lies in the fact that this form of dementia is the only one with any hope of improvement or even cure in relation to appropriate therapy (pharmacological and/or surgical).

Once the diagnosis of Alzheiemer’s disease has been formulated, the next cognitive steps are represented by the administration of neuropsychological and psycho-aptitude tests

These particular questionnaires, which require the work of specialized and experienced personnel, aim not so much to formulate the diagnosis of the disease as to define its stage, the areas of cognitive competence actually involved in the current stage of observation and, conversely, the functional spheres still partially or completely unimpaired.

This practice is most important for the work that will be entrusted to the occupational therapist and rehabilitator, especially if in a context of optimal socialization as is the case in the social welfare communities that work with professionalism and passion in the area.

The quality of life of the patient and his or her family circle is then entrusted to the timeliness and accuracy of this order of assessment, especially to determine the opportunity and the moment when the patient can no longer be, physically and psychologically, assisted within the home.

Diagnostic examinations

Neuroimaging examinations for Alzheimer’s Disease are not particularly useful per se, other than what has been said about the differential diagnosis with multi-infarct dementia and normotensive hydrocephalus: generally functional loss overrides the macroscopic finding detectable on MRI of cortical atrophy, so pictures of obvious loss of cortex texture are usually found when the disease is already clinically evident.

A distressed question that patients often ask the specialist concerns the possible risk of genetic transmission of the disease.

Generally the answer must be reassuring, because almost all Alzheimer’s Diseases are “sporadic,” that is, they occur in families in the absence of any trace of hereditary lineage.

It is true on the other hand that diseases that are indistinguishable, both clinically and anatomo-pathologically from Alzheimer’s Disease with definite hereditary-familial transmission have been studied and recognized.

The importance of this fact also lies in the possibilities that the finding has provided researchers with for the bio-molecular study of the disease: in families with a significant incidence of onset, mutations have in fact been identified that have to do with certain pathological findings typical of diseased cells and that could be strategically exploited in the future in the search for new drugs.

There are also already laboratory tests that can be tried in subjects in whose family line there has been a clear and striking excess of cases of the disease.

Since, however, these are hardly more than 1 percent of cases, I find that in the absence of clear indications of familial disease one should refrain from possible diagnostic abuse dictated by emotionalism.

Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease

Since we do not know the causes of Alzheimer’s Disease, no indications for prevention can be given.

The only scientifically proven finding lies in the fact that, even if the disease arises, continuous mental exercise delays its time course.

The drugs currently used in the treatment of early forms, with a convincing biological rationale, are memantine and acetylcholine reuptake inhibitors.

Although found to be partially effective in counteracting the extent of some cognitive disorders, there are, however, no studies yet establishing their ability to influence the natural history of the disease.

Read Also:

Emergency Live Even More…Live: Download The New Free App Of Your Newspaper For IOS And Android

Parkinson’s Disease: We Know Bradykinesia

Stages Of Parkinson’s Disease And Related Symptoms

The Geriatric Examination: What It Is For And What It Consists Of

Brain Diseases: Types Of Secondary Dementia

When Is A Patient Discharged From Hospital? The Brass Index And Scale

Dementia, Hypertension Linked To COVID-19 In Parkinson’s Disease

Relationship Between Parkinson’s And Covid: The Italian Society Of Neurology Provides Clarity

Parkinson’s Disease: Symptoms, Diagnosis And Treatment

Parkinson’s Disease: Symptoms, Causes And Diagnosis

Alzheimer’s: Fda Approves Aduhelm, First Drug Against The Disease After 20 Years

21 September, World Alzheimer’s Day: Learning More About This Disease

Children With Down’s Syndrome: Signs Of Early Alzheimer’s Development In Blood

Alzheimer’s Disease: How To Recognise And Prevent It